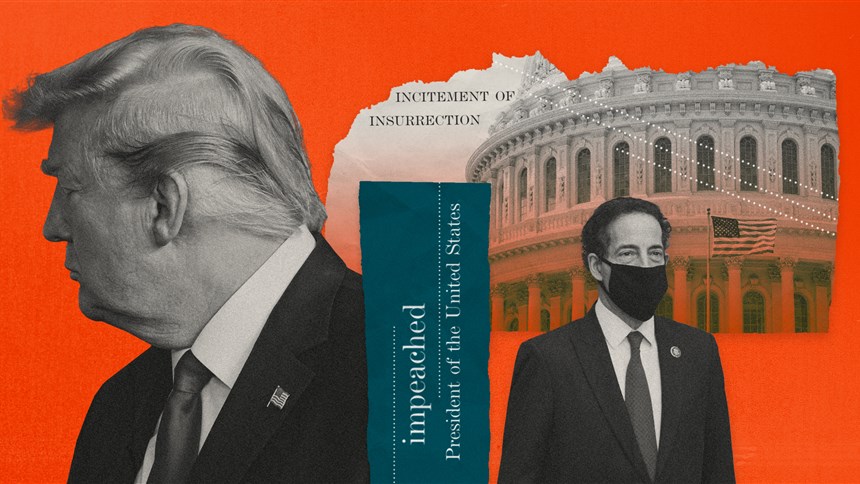

Background

On January 13, 2021, President Trump became the first president in history to be impeached twice. Lawmakers in the House of Representatives voted 232 to 197, approving a single impeachment article which accused Trump of “inciting violence against the government of the United States” while in the pursuit of overturning election results. This happened only a week before Trump was due to leave office. The Senate began an impeachment trial on the matter on February 9, 2021, meaning that the Senate is hearing an impeachment case for a person who is no longer a sitting President or government official. This leads to the question of whether the Constitution allows for impeachment proceedings against a former President.

First, we must turn to the text of the Constitution. Under Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, the House of Representatives “shall have the sole Power of Impeachment,” while Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 grants the Senate “the sole power to try all Impeachments.” Additionally, under Article I, Section 3, Clause 7, “[j]udgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgement and Punishment, according to Law.”

Article II of the Constitution, which governs the executive branch, states in Section 4, “[t]he President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The text of the Constitution does not explicitly address whether a former President may be impeached, and Constitutional scholars are divided on the issue.

Arguments Against Impeachment

Since the text of the Constitution does not directly address the ability to impeach a former President, some scholars believe that it is only possible to impeach a sitting President. Under this way of thinking, scholars rely heavily on the language of Article II, Section 4, which dictates that an impeached and convicted President “shall be removed from office.” The plain text meaning of this is that one must have an office to lose. By definition, the logic follows that a former President is no longer in office, and therefore cannot be removed.

Additionally, Article II limits the people who may be impeached to “[t]he President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States.” It follows that there is no authority in the Constitution to impeach and convict a person who does not fall into the category of President, Vice President, or officer of the federal government. Since Trump is no longer the President or any type of government official at the present, he is no longer subject to “impeachment conviction” by the Senate because the Senate’s power is only to convict an incumbent President.

It is also possible that impeaching a former President could set dangerous precedent for impeaching government officials after they have left office. Some people fear that interpreting the Constitution to mean that persons are subject to impeachment, even if they are not civil officers, would greatly expand the Senate’s authority to prevent future office holding. In this way, impeachment could be used as a political tool to prevent opponents from running for future office.

While a former President has never been impeached before, scholars look to the impeachment of Richard Nixon for guidance. Before the full House of Representatives could vote on Nixon’s impeachment, he resigned from office. Gerald Ford then pardoned Nixon, and the Senate trial never began. However, impeachment is expressly excepted from the President’s pardoning powers. Under Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the Constitution, the President “shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.” This means that members of Congress could have proceeded with impeaching Nixon after his resignation, had they believed it to be possible once he left office.

Arguments for Impeachment

Scholars who argue that impeaching a former president is constitutional tend to focus on the text of Article I of the Constitution. Article I grants power to Congress, and declares that impeachment will be the business of Congress to initiate, try, and punish. Additionally, Article I, Section 3, Clause 7 restricts the possible penalties for impeachment to removal and disqualification, with removal being a minimum requirement following a Senate conviction. Therefore, removal is seen as only a minimum penalty, with disqualification from holding federal office being left as an option for a discretionary consequence.

Additionally, it is argued that there is no barrier to impeaching officials who have committed “high crimes and misdemeanors” while in office, but who have since left office. In other words, there is no requirement that an official have remained an official at every step in the impeachment proceedings. Here, the “high crimes and misdemeanors” alleged in the impeachment articles occurred during Trump’s presidency and are based on actions that culminated in the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol. The House then approved the impeachment article on January 13, 2021, while Trump was still president.

Article I of the Constitution grants the Senate “the sole power to try all impeachments.” The key word here is “all.” Since Trump was President when he was impeached by the House of Representatives, the Senate has the authority to try the impeachment, even if the President has since left office. Therefore, since the impeachment occurred while Trump was still in office, proponents of the constitutionality of the current impeachment proceedings frame the issue as whether the Senate loses jurisdiction if the impeached officer resigns or completes his term before the trial occurs.

However, the penalty for the offense, in this case removal, is not a necessary element or ground for jurisdiction. Instead, it is a consequence of conviction after trial. In civil and criminal court, just because a person cannot be made to suffer a penalty does not mean that person may escape the jurisdiction of the court. Additionally, while the first sanction (removal) is limited to only sitting officers, the second sanction (disqualification), may apply to officers who formerly held positions.

Conclusion

While Constitutional law scholars debate the constitutionality of impeaching a former president, the Senate trial of former President Trump began on February 9, 2021.

Sources

Frank O. Bowman, III, The Constitutionality of Trying a Former President Impeached while in Office, Lawfare (Feb. 3, 2021, 12:42 PM).

Michael Luttig, Once Trump Leaves Office, the Senate Can’t Hold an Impeachment Trial, The Washington Post (Jan. 12, 2021, 5:42 PM).

Keith Whittington, Can a Former President be Impeached and Convicted?, Lawfare (Jan. 15, 2021, 12:22 PM).

Michael McConnell, Impeaching Officials While They’re in Office, But Trying Them After They Leave, Volokh Conspiracy (Jan. 28, 2021, 11:36 AM).

Nicholas Fandos, Trump Impeached for Inciting Insurrection, The New York Times (Jan. 13, 2021).

Noah Weiland, Impeachment Briefing: Trump is Impeached, Again, The New York Times (Jan. 13, 2021).

Philip Bobbitt, Why the Senate Shouldn’t Hold a Late Impeachment Trial, Lawfare (Jan. 27, 2021, 9:01 AM).

U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 5.

U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 6.

U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 7.

U.S. Const. art. II, § 4.

U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2.

Photo courtesy of NBC News.