Since 1949, the Syracuse Law Review has published legal articles, notes, commentaries, and case summaries for the legal community.

Since 1949, the Syracuse Law Review has published legal articles, notes, commentaries, and case summaries for the legal community.

The Law Review has enjoyed working with notable authors and speakers, including:

Nathan Roscoe Pound, Dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1936

Possibilities of Law for World Stability, 2 Syracuse L. Rev. __ (1950)

J. Edgar Hoover, the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Juvenile Delinquency or Youthful Criminality, Syracuse L. Rev. (YEAR)

The Civil Investigations of the FBI, Syracuse L. Rev. (YEAR)

Joseph Biden Jr., 47th Vice President of the United States and 1968 graduate of the Syracuse University College of Law

Who Needs the Legislative Veto?, 35 Syracuse L. Rev. 685 (1984)

Rosel H. Hyde, Former Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (1953-1954; 1966-1969)

FCC Action Repealing the Fairness Doctrine: A Revolution in Broadcast Regulation, 38 Syracuse L. Rev. 1175 (1987)

Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

1991 Commencement Address to the Syracuse University College of Law

Judge Stewart Hancock Jr., Former Associate Judge, New York Court of Appeals

Municipal Liability Through a Judge's Eyes, 44 Syracuse L. Rev. 925 (1993)

Thomas J. Maroney, Former United States Attorney, Northern District of New York

Bowers v. Hardwick: A Case Study in Federalism, Legal Procedure and Constitutional Interpretation, 38 Syracuse L. Rev. 1175 (1987)

Janet Reno, Former Attorney General of the United States (1993-2001)

1998 Commencement Address to the Syracuse University College of Law

Daan Braveman, Dean of the Syracuse University College of Law (1994-2002), Current President of Nazareth College

Chadha: The Supreme Court as Umpire in Separation of Powers Disputes, 35 Syracuse L. Rev. 735 (1984)

Below is an article originally published in 2000 to commemorate the Law Review's 50th year. The article was written by the 1999-2000 editorial staff of the Law Review and details the history journal.

2000

FIFTY YEARS AND BEYOND

Copyright (c) 2000 Syracuse Law Review

Law is the most highly developed of the agencies of social control. It is a need of society to maintain and secure social interests against anti-social self assertion of individuals. But it is a need of the individual also, although he is likely to think only of a need to restrain his neighbor . . . . [law] is a body of norms or models of decision as an authoritative guide to conduct, to judicial decisions and administrative determinations, and as advice to those seeking counsel as to their rights and duties.

--Roscoe Pound, Possibilities of Law for World Stability. [1]

Advisory counsel must, of course, read a great deal. He must read critically all the court opinions--minority as well as majority opinions. He must keep up with current events through the newspapers and journals and books that contribute significantly to thinking on economics and politics.

-- Julius Henry Cohen, On Advice of Counsel.[2]

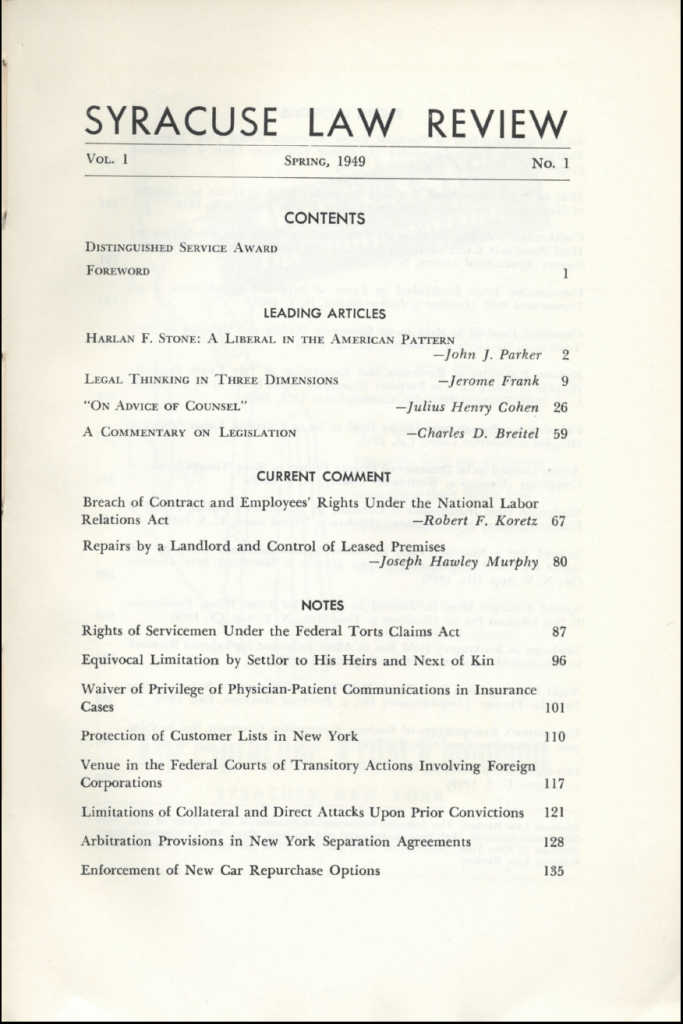

In 1949, $2 bought a subscription to the Syracuse Law Review. The new bi-annual law journal offered leading articles and current commentary by members of the judiciary, practicing lawyers, and law teachers and students. The new law review delved into topics of interest and importance to the legal profession and recent developments discussing noteworthy recent cases. Among the 14 leading articles in Volume 1 were articles on judicial rule-making,[3] civil investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation,[4] law and equity[5] and legal thinking.[6] Our authors in the inaugural volume included J. Edgar Hoover, the legendary director of the FBI[7] and Roscoe Pound, the noted author and dean of Harvard Law *1192 School.[8]

A subscription form bore the statement that the books were “prepared by students of the College of Law, Syracuse University.”[9]

The advertisement’s declaration echoed the sentiment of Dean Paul Shipman Andrews who commented on the Syracuse Law Review’s founding as a “creditable addition” to the crowded field of legal scholarship.[10] The Dean, in his foreword, also expressed gratitude to the Syracuse University community, alumni and the college of law students who “performed the arduous task of creating the Review.” Dean Andrews continued:

Of one thing the Review is confident: that it will constitute a worthwhile tool for the better training of the student body (all of whom may submit notes or comments in competition for the privilege of publication) in the skills of legal writing and research. This is perhaps the primary objective of the Syracuse Law Review.[11]

The field may have been crowded, and growing,[12] but the time had arrived for the Syracuse Law Review.[13] The new law review was forged to provide Syracuse College of Law students with the unique[14] and immensely valuable experience of publishing a law review[15] while thrusting the Syracuse name into the world of legal scholarship.[16]

The faithful members of the Syracuse Law Review fulfilled Dean Andrews’ prophesy over the past five decades as they researched, wrote and edited this publication. Likewise, the Syracuse Law Review has fulfilled its duties as a creditable source of legal scholarship for practicing attorneys, academics and Syracuse law students who earned their way onto this Review.[17]

This law review has met the needs of our readers by chronicling and reporting recent developments in the law on the state, national and global levels.[18] Over the years, scholars’ articles have proposed changes and improvements to the law. To date, even the United States Supreme Court referred to this publication, citing the Review in 11 different court opinions.[19]

Likewise, the Syracuse Law Review has contributed to scholarship and served as a record of the events at Syracuse College of Law and the university itself by sponsoring symposia,[20] publishing commencement speeches,[21] distinguished service awards[22] and the dedication of new buildings.[23]

One of our most influential contributions to legal scholarship came in 1962 when the Syracuse Law Review inherited the honor of publishing the Annual Survey of New York Law.[24] In his foreword, Dean Ralph E. Kharas paid tribute to the other law schools in New York state and graciously accepted the torch from the New York University Law Review which had published the Annual Survey since 1947.[25] The Annual Survey, he wrote: “has made a substantial contribution to the Empire State lawyers in their task of keeping up with the law.”[26]

Over the years, the judges of the New York Court of Appeals regarded the Survey as a useful record and reflection of the nation’s common law tradition.[27] The Survey chronicled developments with state-wide, national and international implications,[28] marked the law’s progression[29] and served as an annual “report card” for New York’s courts and judges.[30]

Over the years, the judges of the New York Court of Appeals regarded the Survey as a useful record and reflection of the nation’s common law tradition.[27] The Survey chronicled developments with state-wide, national and international implications,[28] marked the law’s progression[29] and served as an annual “report card” for New York’s courts and judges.[30]

In his foreword to the 1992 Survey, Judge Joseph W. Bellacosa, wrote:

This Syracuse Law Review Survey of New York Law for 1992 is a fine way station in that journey towards the destination of better understanding and achievement of the ideal. It focuses the reader’s eye and mind on a connected, comprehensive examination of seemingly disparate strands of justice, as actually delivered for better or for worse. This annual assessment educates the reader and renders an accounting of, and to the judiciary. The goal of this search, somewhat like Diogenes, is to grope for and discover an improved rule of law and a fairer system for delivering justice during ensuing *1196 years.[31]

Publishing the annual Survey generated praise on the law review’s 20th anniversary in 1969. United States Attorney General John N. Mitchell wrote a letter congratulating the law review on its 20th anniversary, specifically referring to the annual survey as “helpful to practicing attorneys, judges and scholars who are interested in following the development of law in our state.”[32]

In 1969, the editors of volume 20 published a prototypical example of an ideal law review linking the past with the future. Volume 20 included an article written by Osmond Fraenkel, who also wrote for the first edition.[33] As they looked back to the founders, who exemplified the high level of academic merit to found this Review, the editors looked forward as well. Those editors sent a message to future editors: “During the next twenty years, we hope the Syracuse Law Review will continue to explore the legal frontier . . . .”[34]

Those editors stepped toward the legal frontier with two visionary articles: one involving employment discrimination;[35] the other space law.[36] The space law article, written by Syracuse Law Professor George J. Alexander was the outgrowth of a Syracuse University study conducted under a grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and was presented at the XIth International Colloquium on Space Law.[37]

*1197 At a time when the international space race escalated and men walked on the moon, the article addressed many of the legal implications associated with space exploration including property rights in space and on Earth,[38] national security in outer space,[39] liability for disasters,[40] NASA’s jurisdiction,[41] and workplace safety for astronauts.[42]

Professor Alexander concluded his piece:

The domestic legal problems facing the United States’ space program are, admittedly, not problems of grand proportions but they are real and serious nonetheless. What’s more, they will not patiently await studied answers once the contingencies manifest themselves. If answers are to be better than makeshift, they should come soon. We at the Syracuse project hope we can be involved in finding them.[43]

Volume 20 exemplified the purpose of this law review by balancing legal history with a vision of the future legal landscape.

Editorial boards over the years provided exemplary models and worthy successors.[44] For example, in 1960, with Volume 12, the editorial board took the step to transform the law review into a quarterly publication.[45] After a two-year effort, in 1984, Volume 35, became the first Syracuse Law Review published using computerized word processing *1198 technology.[46] The editor’s note stated that the use of the new technology would allow the staff to publish a timelier book with greater editorial control.[47] Computers permitted the editors to publish more pages and incorporate late changes, additions and corrections.[48] The technology enabled the editors to better serve our readers and subscribers.[49]

In 1989, on the law review’s 40th anniversary, the editors referenced the profound and complex changes in the legal world since Volume 1.[50] Despite the emergence of new legal frontiers in a world transformed by technology, the editors proclaimed that the Syracuse Law Review’s mission remained constant: to provide a forum for exploring developments in statutory and common law while identify problems and proposing solutions.[51]

Today, Volume 50 is born in a world of instantaneous change. Business, political, social and technological forces alter the world on a minute-by-minute basis. Laws and regulation must conform and shape those forces at an equally instantaneous pace. Legal scholarship must also keep pace, yet remain a refuge for accurate information and innovative propositions.[52] The Syracuse Law Review has and will meet those goals.[53]

Like our predecessors in Volume 20, this book seeks to mesh the past, present and future. This book highlights several areas of legal development over the years as perceived by a panel with close ties to the Syracuse Law Review, our alumni.[54]

Even as legal observers note the explosion of specialized law journals and critics foretell of the demise of the general interest law journal,[55] the Syracuse Law Review will continue.[56] Our articles contribute to the legal landscape while our student notes provide burgeoning legal scholars with the unique opportunity to hone legal research and writing skills while contributing to the legal community.

Technology and computers have had a tremendous impact on the legal publishing world.[57] The Syracuse Law Review has kept pace with these changes and will continue to do so. The means of conveyance may change, but the information and scholarship under the Syracuse Law Review banner will continue.

[1] 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 337, 337 (1950).

[2] 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 26, 57 (1949).

[3] Charles E. Clark & Charles Alan Wright, The Judicial Council and the Rule-Making Power: A Dissent and A Protest, 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 346 (1950).

[4] John Edgar Hoover, The Civil Investigations of the FBI, 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 380 (1950).

[5] Ralph E. Kharas, A Century of Law-Equity Merger in New York, 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 186 (1949).

[6] Jerome Frank, Legal Thinking in Three Dimensions, 1Syracuse L. Rev. 9 (1949).

[7] Hoover, supra note 4.

[8] Pound, supra note 1.

[9] This advertisement was found in the non-paginated advertisement pages in the front of the third of the three books published in the first volume in 1949-50. The subscription advertisement stated the cost, $2 and the frequency of publication, twice a year.

[10] Dean Paul Shipman Andrews, Foreword, 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 1, 1 (1949).

[11] Id.

[12] At the founding, many law schools were entering the crowded field of legal scholarship. In 1949, there were fewer than 70 law reviews published in the United States. 8 Index to Legal Periodicals (1946-49). See also Michael L. Closen & Robert J. Dzielak, The History and Influence of the Law Review Institution, 30 Akron L. Rev. 15, 38 (1996).

[13] See Asher Bogin, Reflection, 50 Syracuse L. Rev. 1201, 1201-02 (2000). See also Michael I. Swygert & Jon W. Bruce, The Historical Origins, Founding, and Early Development of Student-Edited Law Reviews, 36 Hastings L.J. 739, 779 (1985) (“The impact on the academic world of the first successful student-edited law review is reflected in the creation of similar periodicals at other institutions. In the legal world at large, its articles soon began to affect judicial decisions and legislative deliberations.”).

[14] Chief Justice Earl Warren articulated perhaps the most famous praise of the law review as an institution by calling it “most remarkable institution of the legal world”:

To a lawyer, its articles and comments may be indispensable professional tools. To a judge, whose decisions provide grist for the law review mill, the review may be both a severe critic and a helpful guide. But perhaps most important, the law review affords invaluable training to the students who participate in its writing and editing.

Earl Warren, Messages of Greetings to the U.C.L.A. Law Review, 1 UCLA L. Rev. 1, 1 (1953).

[15] See James W. Harper, Why Student-Run Law Reviews?, 83 Minn. L. Rev. 1261, 1274-75 (1998).

[16] See Swygert & Bruce, supra note 13, at 779. In the first decades of the 20th Century, the law review tide swept the country as many other law schools started and nurtured student-edited periodicals... factors, however, contributed significantly to the increase in the number of law reviews. Most important, the law schools recognized the educational benefits of such student-run operations. In addition, the existence of a law review was, and still is, considered to be the mark of a mature educational institution, one whose reputation is partially based upon the students’ academic product. Moreover, law schools made a positive statement about their commitment to legal scholarship by including a law review in their curricula.

Id.

[17] See Roger C. Cramton, “The Most Remarkable Institution”: The American Law Review, 36 J. Legal Educ. 1, 4-5 (1986). The author credits law review membership as part of the American democratic tradition because law review membership has been based on academic performance: “as a meritocracy whose talent justified the honor.” The author wrote:

The emergence of the student-edited law review has other important relationships to social and intellectual developments in the United States. In addition to its connection to intellectual currents in legal theory and legal education, the special status conferred by law-review participation was then viewed as consistent with democratic principles.

Id. at 4.

[18] See Jordan H. Liebman & James P. White, How the Student-Edited Law Journals Make Their Publication Decisions, 39 J. Legal Educ. 387, 397 (1989). The authors wrote:

Critics are correct that virtually no one reads issues of generalist law reviews as they do news magazines or even trade publications. That is not to say they are unused or lack influence. Rather they serve as reference materials waiting quietly in libraries for scholars, judges, students, and practitioners who need help in solving legal problems and in selling their solution to the world.

Id.

[19] As of August 2000, the United States Supreme Court cited articles from the Syracuse Law Review in 11 judicial opinions. The Court cited an article from the first edition written by one of the first editors, Asher Bogin. See Note, Rights of Servicemen Under the Federal Tort Claims Act, 1 Syracuse L. Rev. 87 (1949); see also Asher Bogin, Reflection, 50 Syracuse L. Rev. 1201 (2000). The following is a list of the Court’s opinions citing the Syracuse Law Review: Calderon v. Thompson, 523 U.S. 538 (1998); Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361 (1989); Pierce v. Underwood, 487 U.S. 552 (1988); Douglas v. Seacoast Prods., 431 U.S. 265 (1977); Time Inc. v. Firestone, 424 U.S. 448 (1976); United States v. Ash, 413 U.S. 300 (1973); United States v. White, 401 U.S. 745 (1971); National Woodwork Mfrs. Ass’n v. NLRB, 386 U.S. 612 (1967); Russell v. United States, 369 U.S. 749 (1962); United States v. Spector, 343 U.S. 169 (1952); Brooks v. United States, 337 U.S. 49 (1949).

[20] See, e.g. Symposium, The Problems of Professional Responsibility, 12 Syracuse L. Rev. 429 (1961); Symposium, International Law, 13 Syracuse L. Rev. 513 (1962); Symposium, Law and Psychiatry, 14 Syracuse L. Rev. 547 (1963); Symposium, Youth and the Judicial System, 15 Syracuse L. Rev. 625 (1964); Symposium, The Law of International Claims, 16 Syracuse L. Rev. 719 (1965); Symposium, The Legal Rights of the Mentally Retarded, 23 Syracuse L. Rev. 991 (1972). See also Celebrating The New York Court of Appeals 150th Anniversary, 48 Syracuse L. Rev. (1998).

[21] See Janet Reno, Syracuse University College of Law Keynote Commencement Address, 49 Syracuse L. Rev. 1247 (1999); Theodore A. McKee, Syracuse University College of Law Keynote Commencement Address, 50 Syracuse L. Rev. 1055 (2000). See also William O. Douglas, Remarks on Law Day 1973, 24 Syracuse L. Rev. 1209 (1973).

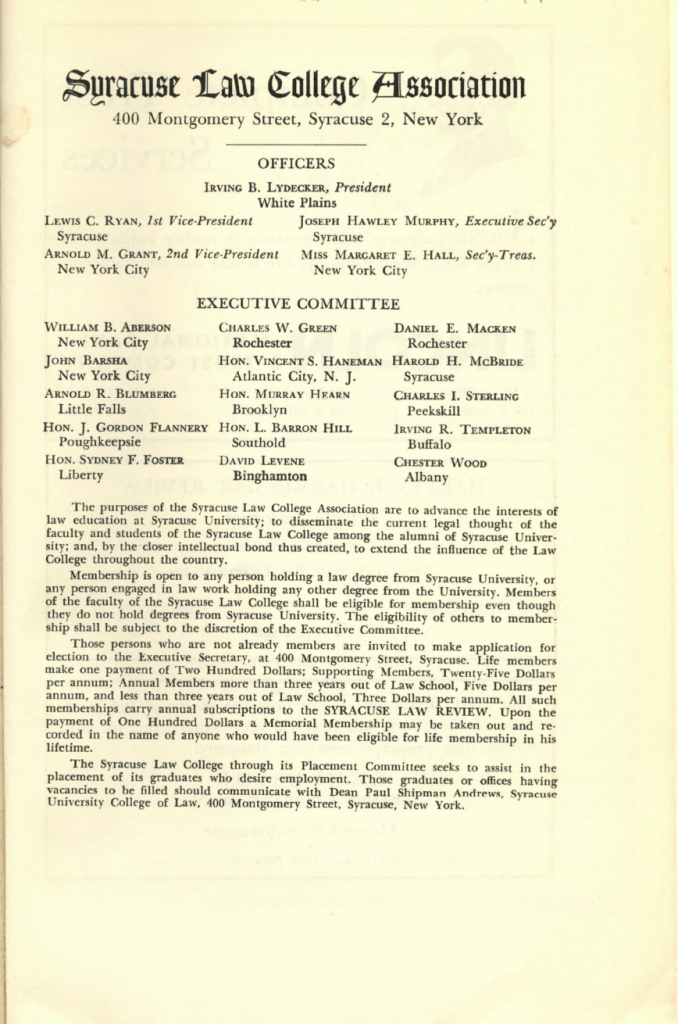

[22] For example Edmund Harris Lewis, a 1909 Syracuse College of Law alumnus who served as Associate Judge of the New York Court of Appeals received the first annual Distinguished Service Award in 1949. See 1 Syracuse L. Rev. (1949).

[23] In 1954, the law review published the thirteen pages of text including photographs of the new Ernest I. White Hall, the College of Law’s new home on campus. Additionally, this package included publication of convocation speeches by Robert Houghton Jackson, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Arthur T. Vanderbilt, Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court and later dean of New York University Law School, Edmund H. Lewis, Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, Charles E. Clark, Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and Jane White Canfield, daughter of E.I. White. See 6 Syracuse L. Rev. (Spring 1955).

[24] Dean Ralph E. Kharas, Foreword, 14 Syracuse L. Rev. 145 (1962).

[25] Id. Dean Kharas quoted the foreword by NYU Dean Arthur Vanderbilt in NYU’s premier Survey of New York Law:

As the demands of his professional work grow heavier year by year, the output of the legal authority he is supposed to know as “counsel learned in the law” likewise increases by leaps and bounds.

[26] Id.

[27] Judith S. Kaye, Foreword: State Courts in Our Federal System: The Contribution of the New York Court of Appeals, 1994-1995 Survey of New York Law, 46 Syracuse L. Rev. 217, 217-18 (1995). In her introduction to the Survey, Judge Kaye discussed Justice Brennan’s reflection on state courts’ role democracy and resolving disputes. State courts, Judge Kaye, noted handled ninety-seven percent of the countries legal disputes. “Today’s state court cases at times represent the battlefield of first (and last) resort in social and cultural revolutions of a distinctly modern vintage.” Id.

[28] Howard A. Levine, Foreword: Deciding Cases in “The Common Law Tradition”: A Productive and Innovative Year for the Court of Appeals in Business and Commercial Litigation, 1996-97 Survey of New York Law, 48 Syracuse L. Rev. 355, 356-57 (1998) (“This Survey Year presented a considerable number of important commercial and business law cases having statewide, national and even international implications.”).

[29] Stewart F. Hancock, Jr., Foreword: Constancy Through Turbulent Times, 1995-96 Survey of New York Law, 47 Syracuse L. Rev. 291, 291 (1997) ( “As in previous annual Surveys, the cases reviewed in this volume demonstrate the principled and orderly progress of the common law... in its continuous development and change to serve the needs of society.”).

[30] Sol Wachtler, Foreword, 1991 Survey of New York Law, 43 Syracuse L. Rev. 1, 1 (1992):

The annual publication of the Syracuse Law Review Survey of New York is a welcome occasion for contemplating the legal developments of the past year. For those of us who have a hand in those developments, the Survey is a yearly evaluation, something like a report card. Although it is invariably unfavorable in some respects, we nevertheless value the assessment of the State of New York law by scholars and practitioners with experience and expertness in the areas that our decisions affect. It is enlightening not only to read what the authors have to say about our decisions, but also to see which decisions capture their attention.

[31] Joseph W. Bellacosa, Foreword, 1992 Survey of New York Law, 44 Syracuse L. Rev. 1, 2 (1993).

[32] The full text of the letter read:

President Nixon and I would like to congratulate the Syracuse Law Review on its twentieth anniversary. During the past two decades, the Review has grown both in size and in excellence. The annual survey of New York law has been particularly helpful to practicing attorneys, judges and scholars who are interested in following the development of the law in our state. You may be proud of your contribution to legal literature.

Letter from John N. Mitchell, Attorney General, to Howard Siegel, Editor, Syracuse Law Review (June 16, 1969) (published in single edition copy of 20 Syracuse L. Rev. (Summer 1969)).

[33] Osmond K. Fraenkel, The Impact of Mootness, 20 Syracuse L. Rev. 835 (1969).

[34] This note from the Editorial Board was published in the unnumbered preliminary pages of the August edition of 20 Syracuse L. Rev. (Aug. 1969). The note stated: “The ever growing complexities of the law have created new and difficult challenges for any organization which purports to discuss current legal developments.” Id.

[35] William B. Gould, Non-Governmental Remedies for Employment Discrimination, 20 Syracuse L. Rev. 865 (1969).

[36] George J. Alexander, The Legal Frontier in the United States Space Program, 20 Syracuse L. Rev. 841 (1969).

[37] Id.

[38] Id. at 846-53.

[39] Id. at 855.

[40] Id. at 853-58.

[41] Id. at 858-60.

[42] Id. at 860-64.

[43] Id. at 864.

[44] In 1969, New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller congratulated the law review on its 20th anniversary, describing the law review as a “distinguished publication.” The governor added: “My compliments to all concerned upon the high level of academic merit that you have achieved.” Letter from Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor of New York, to Howard Siegel, Editor, Syracuse Law Review, (May 22, 1969) (published in single edition copy of 20 Syracuse L. Rev. (Summer 1969)).

[45] The editor’s note read:

The College of Law announces with pride that with this issue the Syracuse Law Review will be published quarterly instead of semi-annually.

The first issue of the Syracuse Law Review as published in the spring of 1949. In eleven years its pages have been open to scholarly and practical writing for lawyers; but more particularly, it has afforded a stimulus to students in the College of Law to improve their research methods and their competency in writing.

It is our hope that the quarterly publication of the Syracuse Law Review will bring to subscribers matters of interest while they are current. We are assured that quarterly publication will strengthen the program of the research and writing for students in the College of Law.

John T. Hunter, Editor’s Note, 12 Syracuse L. Rev. (1960).

[46] Kirk M. Lewis & E. David Hoskins, Editor’s Note, 35 Syracuse L. Rev. (1984).

[47] Id. The note stated:

Several benefits will accrue, we hope from the use of this technology. Full computerization will result in timelier publication, greater editorial control, and increased flexibility in accommodating late changes. Also, the savings resulting form computer use have allowed the Law Review to publish a greater number of pages. This increased flexibility will better enable Syracuse Law Review to serve the needs of the legal community.

The transition to computer technology has been difficult at times, and could not have been done without the efforts of many people. We would like to thank last year’s Editorial Board, which initiated the conversion to computer... and this year’s editorial board and staff who have endured both human and computer error.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] Jeffrey R. Capwell & Peter L. Powers, Editors’ Note, 40 Syracuse L. Rev. (1989).

[51] Id. The Editors’ Note stated:

This issue is dedicated to the forty-year tradition of the Syracuse Law Review and represents one of the most comprehensive issues to date. Nineteen articles are contained in the 1988 Survey, including two new articles on Local Government and Professional responsibility....

This year’s editorial board is proud to add another chapter to the Survey’s continuing tradition of legal scholarship. We are ever mindful of the value and importance of the Survey to legal education and legal practice in New York. With knowledge of this challenge, we have endeavored to uphold and improve the high standards evident in past issues of the Survey....

[52] See Leibman & White, supra note 18, at 397.

[53] 1989, the law review emerged with a blue cover and an ambitious statement:

The Syracuse Law Review, entering its fifth decade, looks out upon a world starkly different from that which our inaugural issue faced. The past forty years have seen the development of highly complex technology, different and sometimes unusual family, corporate and government structures, regulation and deregulation of major industries, and changing concepts of property and civil rights. These developments, to name only a few, have produced myriad changes in the law. yet the goals of the Syracuse Law Review have maintained relatively constant.

Laurel J. Eveleigh & Rebeca Sanchez-Roig, Editor’s Note, 40 Syracuse L. Rev. (1989) (third book).

[54] See Wendy S. Loughlin, Syracuse Law Review Celebrates 50 Years of Contributions to the Law Community, The Syracuse Record, Apr. 24, 2000, at 3.

[55] See Tracey E. George & Chris Guthrie, Symposium, An Empirical Evaluation of Specialized Law Reviews, 26 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 813, 821-24 (1999).

[56] Leibman & White, supra note 18, at 387 (“Because they are generally older than the school’s specialty reviews, they have had more time to accumulate the petina of prestige.”).

[57] See generally Bernard J. Hibbitts, Last Writes? Reasessing the Law Review in the Age of Cyberspace, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 615 (1996); Conference: The Development and Practice of Law in the Age of the Internet, 46 Am. U. L. Rev. 327 (1996).