Written By: Maddy Cittadino

Written By: Maddy Cittadino

Introduction

On January 22, 1973, the United States Supreme Court held that a woman has a constitutional right to abortion in Roe v. Wade. On June 24, 2022, that decision was overturned by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. For the general public, Roe has existed as a case solely dealing with abortion; however, following the Dobbs decision, Roe’s implications on other non-abortion rights, such as same-sex marriage, same-sex sexual conduct, and contraception have become an increasing concern.

Background on Roe v. Wade

Jane Roe was a single, pregnant woman from Texas who wanted to get an abortion from a competent, licensed physician. However, Roe was unable to do so pursuant to Articles 1191–1194 of the Texas Penal Code, which made it a crime to receive or attempt an abortion except for the purpose of saving the woman’s life, as Roe’s life was not threatened by the pregnancy. Roe then brought suit, claiming that the Texas statutes were unconstitutionally vague and violated her right to privacy.

Substantive Due Process and the Right to Privacy

The United States Constitution does not explicitly grant a right of privacy. However, the Court has adopted a doctrine of implied fundamental rights, referred to as Substantive Due Process. The Fourteenth Amendment states, in part, “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” While Procedural Due Process is concerned with the proper steps and procedures being taken by the government before life, liberty, or property is deprived, Substantive Due Process focuses on the Framer’s use of the word “liberty,” and whether there are fundamental rights implied within it. In other words, on the one hand, “liberty” can be understood as a general principle of freedom, or, on the other hand, “liberty” can also be understood as encompassing specific fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy. At the heart of Substantive Due Process is questioning whether there are certain implied fundamental rights that one must have to fully exercise and enjoy the Constitution’s grant of liberty.

In general, if a right is considered fundamental under the Constitution, a high burden is placed on the government if it attempts to invade that right. When a fundamental right is implicated, the government is required to show that it has a compelling state interest to invade that right, and that the government’s means of invading that right are necessary and narrowly tailored to that specific state interest. To determine whether a right is fundamental, the Court will look at history and tradition to determine whether the right is essential to our Nation’s understanding of “ordered liberty.” Through various opinions, the Court has recognized a right of personal privacy, which has been extended to other activities such as inter-racial marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, and child rearing.

The Court in Roe reaffirmed the doctrine of Substantive Due Process and the fundamental right of personal privacy, holding that the right of personal privacy “is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy,” but declined to make that right absolute. In other words, the Court rejected the argument that a woman is “entitled to terminate her pregnancy at whatever time, in whatever way, and for whatever reason she alone chooses.”

In deciding that the fundamental right of personal privacy encompasses a woman’s decision to get an abortion, the Court was then required to determine whether the State has a compelling state interest to limit that right. After analyzing the history of abortion in the United States and the State’s interest in health, safety, and potential life, the Court concluded:

- Prior to the first trimester, the decision of whether to get an abortion is left solely to the physician’s medical judgment;

- After the end of the first trimester, the State can regulate abortion to promote its interest in the mother’s health in a manner that is related to the mother’s health; and

- After viability, the State can regulate or ban abortion pursuant to the State’s interest in potential life, except for when abortion is medically necessary.

The Court in Roe stated that they were leaving “the State free to place increasing restrictions on abortion as the period of pregnancy lengthens, so long as those restrictions are tailored to the recognized state interests.”

Other Substantive Due Process Decisions

In Obergefell v. Hodges, the Court, after recognizing the right to marry as a fundamental right, relied on Substantive Due Process and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to hold that same-sex marriage is constitutionally protected. In Griswold v. Connecticut, the Court relied on the “penumbras” of the Bill of Rights to establish a right to personal and marital privacy that encompasses the use of contraceptives and prevents States from forbidding their use. Finally, in response to a Texas law criminalizing same-sex sexual conduct, the Court found Substantive Due Process to encompass private sexual activity between consenting adults in Lawrence v. Texas. In each of these decisions, the Court performed a similar analysis as the one performed in Roe by looking at the proposed right’s historical and cultural context to determine whether that right can be considered “fundamental” and therefore within the Constitution’s heightened protection.

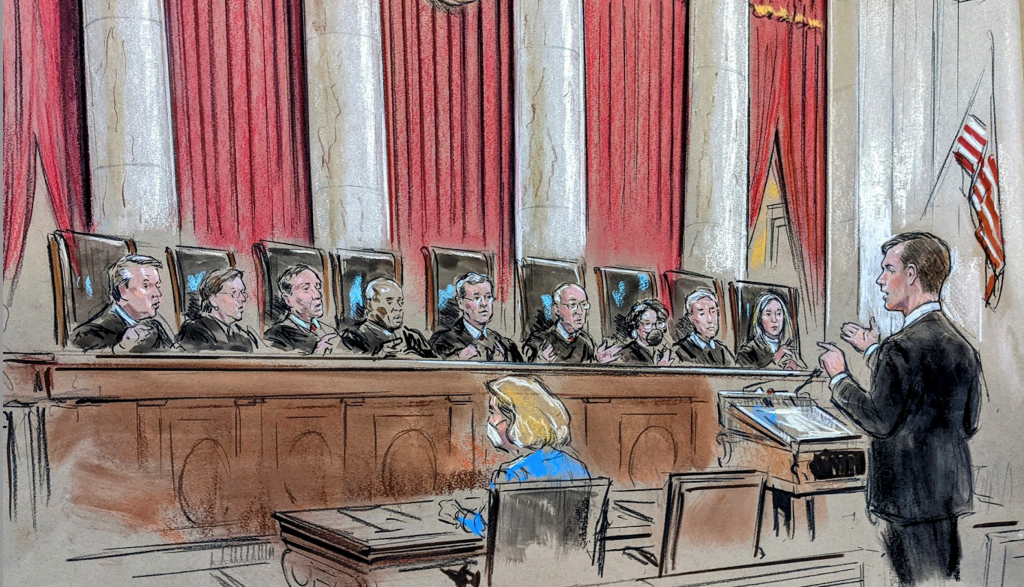

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization: The Decision

Before the Court in Dobbs was a Mississippi law that prohibited abortion after fifteen (15) weeks (before viability), except if there was a medical emergency or severe fetal abnormality, which violated Roe v. Wade. Therefore, the Court was able to use this case to reconsider the Court’s 1973 decision in Roe. In holding that the Constitution does not provide a right to abortion, the Court overruled Roe. First, the Court held that the right to an abortion is not a fundamental right recognized by neither the Constitution, our Nation’s history and traditions, nor encapsulated by other, broader rights. Then, the Court concluded that traditional stare decisis (preserving the Court’s prior decisions) factors weigh against upholding Roe—namely, the nature of the Court’s error in Roe; the quality of the Court’s reasoning in Roe; the workability of the rule set forth in Roe; Roe’s effect on other areas of law; and the reliance interests on the Roe decision.

Of course, the Court’s decision in Dobbs is much more nuanced than the summary provided here. However, the aftermath of the Dobbs decision spans beyond abortion by calling into question other decisions that were decided on similar grounds to Roe—Obergefell (same-sex marriage), Lawrence (same-sex sexual conduct), and Griswold (contraceptives)—and whether the overturning of Roe presents a similar fate for these decisions.

The majority opinion in Dobbs, authored by Justice Alito, rejects the argument that these other precedents are at risk by the Dobbs decision. Justice Alito argues that abortion is fundamentally different than marriage, intimacy, or procreation because it deals with “potential life,” and therefore “[n]othing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” On the other hand, Justice Thomas, in his concurring opinion, states that “in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell. Because any substantive due process decision is ‘demonstrably erroneous’…we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents.” The dissenting opinion of Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan offer a much more heightened concern for the fate of these precedents. The dissenting justices argue that the basis for overturning Roe—that “the right to elect an abortion is not ‘deeply rooted in history’”—can theoretically be applied to the use of contraceptives, same-sex marriage, and private intimacy.

Conclusion

The overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’ Health Organization could potentially have implications spanning far beyond the legality of, and access to, abortions. Dobbs has brought many issues to the forefront—abortion, women’s rights, Substantive Due Process, fundamental rights, stare decisis, the proper role of the Court, and what should be left up to individual states—and therefore impacting everything from the individual, to broad constitutional questions and analyses.

Sources:

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. _ (2022).

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003).

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. _ (2015).

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).